The First Olympic Champion

Did you know that James B. Connolly — a spirited son of poor Irish immigrants from South Boston and Knight of Columbus — became the first modern Olympic champion when he won the triple jump event in 1896?

Athlete, author and Knight of Columbus James B. Connolly was the first to win in the modern Olympic games

By Andrew J. Matt. Originally posted on kofc.org on 7/23/2021

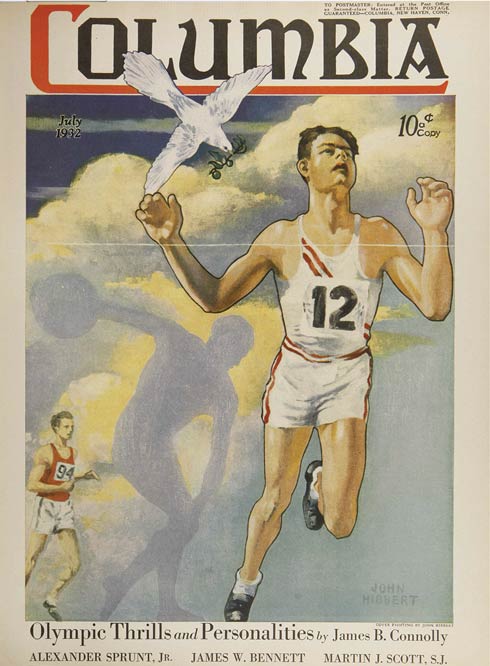

The issue also featured an article from Connolly about his time in the Olympics.

One of the most distinguished — and improbable — victories in Olympic history occurred 125 years ago, when James B. Connolly won the first event of the 1896 Olympic Games. A feisty and energetic 27-year-old son of poor Irish immigrants from South Boston, Connolly became the first Olympic champion in more than 1,500 years.

Abolished in 393 A.D. by Emperor Theodosius I, the Olympic Games lay dormant until their 1896 revival by Pierre de Coubertin, a French nobleman. As Europeans were expected to dominate all the events, the United States fielded only a dozen athletes, mainly Harvard and Princeton men. To qualify, all the Americans had to do was fill out an entry form and pay their way across the ocean. Connolly, the American record holder in the triple jump, was determined to join the team of ’96.

One of 12 children and the sixth of 10 sons, Connolly was born Oct. 28, 1868. His father was a fisherman, while his mother raised the children and translated Gaelic poetry. Though he never completed high school, Connolly was a man of boundless enterprise and imagination. After working as a clerk in a Boston insurance company, he joined the Army Corps of Engineers in Savannah, Ga., where he founded a Catholic sports club, wrote a sports column for a weekly newspaper and established a bicycling business. In 1890, he won the national triple jump championship. Bright but uneducated, he took Harvard’s entrance exam in 1895 and was accepted to study in the fall.

“I was a freshman at Harvard,” Connolly later recounted, “when I saw in the papers that the Olympics were to be revived. Right away, I wanted to go. I was National A.A.U. hop, step and jump champion, and I asked Harvard if I could represent them at the Games. They said if I left I’d have to resign and might not get back in school when I returned. So I quit.”

Returning to his roots, Connolly received sponsorship from his Suffolk Athletic Club of South Boston. With the help of his family’s Catholic parish, he then managed to raise enough money for a ticket on the U.S.S. Fulda, a Naples-bound steamer that would carry him and most of his Olympic teammates across the Atlantic for the start of the Games on Easter Monday, April 6.

Having calculated that they would have 12 days to get acclimated in Athens, the young Americans trained as much as they could on the deck of the ship. After 16 straight days of travel, they arrived at their destination only to discover with shock that — according to the Julian calendar used in Greece — it was actually Easter Sunday, April 5. Connolly’s event was slated to follow the opening ceremony, the very next day.

Eighty thousand spectators filled the stadium as the sleep-deprived triple jumper walked out to the sandpit. There were no trials; three jumps would determine the winner. On his final turn, Connolly leaped 45 feet before the astonished crowd.

Prince George of Greece, the chief fields judge, announced the results of the first Olympic event. “You are the victor,” he told Connolly. “You have beaten the second man by a meter.” The crowd erupted with “Nike! Nike!”— “Victor! Victor!” — as a band broke out into the Star-Spangled Banner and the American flag was raised over the stadium. Connolly later described the sensation: “I went floating, not walking, floating across the stadium arena on waves that sounded like a million voices and two million hands cheering and applauding.”

Connolly was then crowned with an olive wreath and received a silver medal. (In the 1896 Olympics, only the top two received medals; silver for first and bronze for second.) He went on to take second place in the high jump and third place in the long jump. The next year in New York, Connolly would set a new triple jump record with a mark of 49 feet, which stood for 13 years and was not matched in Olympic competition until 1924.

Connolly’s colorful career continued back in Boston, where he wrote for a living and joined the Knights of Columbus as a member of Back Bay Council 331. At the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898, he enlisted with the Ninth Massachusetts Infantry and fought at San Juan Hill in Cuba, publishing war reports in the Boston Globe. He married Elizabeth Hurley in 1904 and later had a daughter, Brenda. During World War I, he covered U-boat action for Collier’s magazine, met Pope Pius X and later reported on the Irish War of Independence. His writing also appeared in magazines like the Saturday Evening Post, Harper’s and Columbia.

Renowned for his salty temperament, Connolly authored more than 25 novels and 200 short stories based on his extensive maritime travels, which included trips with Gloucester fishermen and German fleets in the Baltic, Arctic whaling expeditions and a trans-Atlantic voyage in a racing yacht. He was dubbed “America’s best writer of sea stories” by Joseph Conrad and also admired by T.S. Eliot and President Teddy Roosevelt. James Brendan Connolly died in New York on Jan. 20, 1957, at the age of 88.